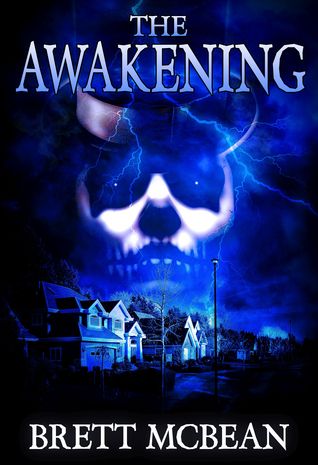

The Awakening

Brett McBean

Bloodshot Books

2016

Originally Published 2012

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Brett McBean’s coming-of-age supernatural thriller, The Awakening, is a fascinating read for several reasons, one being that in some ways it shouldn’t work as well as it does…it seems structurally flawed, and yet it is both strongly compelling and emotionally impelling.

It consists of three intertwining narratives, at times somewhat awkwardly joined through long passages of uninterrupted monologue—yet each intriguing in its own right. At the core of each is fourteen-year-old Toby Fairchild, a typical boy in a typical Midwestern town, Bedford, Ohio (it’s tempting to see an allusion to another typical small town from It’s a Wonderful Life). This is the summer of his awakening: to hope and loss; to the discovery that his parents and other adults are all-too-human; to the undeniable stirrings of romance and sexuality; in short, to all the stresses of incipient adulthood…and much more.

The first portion of The Awakening works toward unraveling the secret of the mysterious Mr. Joseph, an ancient-seeming Haitian, deformed and scarred by some long-ago tragedy, who is the focus of the town’s fears and xenophobia. After twenty years in Bedford, he is still unknown, distrusted, avoided. Circumstances force Toby to draw closer to the old man, to discover a past that would forever alter the boy’s understanding of life and death.

The final portion of the novel deals directly with death—the sudden, vicious death of another boy—and Toby’s increasing involvement in uncovering the murderers. McBean does an excellent job of re-creating the abruptness of tragedy and tracing its consequences for all concerned, particularly for Toby. As emotions become raw and fear escalates, Toby’s need to reconcile death with the world he has known becomes enmeshed in contradictions of love and hate, of affection and antipathy, of acceptance and of racism and bigotry.

Linking the two is Mr. Joseph’s story, told in first-person through several extended passages, often broken up using devices such as telephone calls or someone knocking on a door…perhaps the most artificial part of the narrative. Yet his story is captivating. He is, after all, a zombi (not a spoiler, particularly; that much is hinted at by the cover text). Here McBean introduces a key horror motif and an over-riding metaphor. Mr. Joseph is no flat film caricature, craving brains, shuffling and moaning, covered in blood and rotting. Those, he points out are “zombies”—and the spelling indicates an important difference. Instead, Mr. Joseph harkens back to the original, pre-Hollywood, Haitian image of the dead; their souls stolen at the point of death and henceforth slaves to their bocor master. Part of his story concentrates on the mindlessness, the emptiness of such slavery, with the unspoken awareness that many in Bedford are almost as mindless, as empty, in their acceptance of social constructs.

But Mr. Joseph’s story goes beyond that to suggest an even deeper level of suffering. He is a zombi savane, one who has been in part redeemed and called back to life…an unending life of suffering and pain. While now alive, he is still in most important senses a zombi, a slave to his past, forever (literally) mourning the loss of his family, drawn to the promise of true death but incapable of attaining it. Through his interactions with Toby, Toby gains the strength to embrace truth and grow, while Mr. Joseph simultaneously gains the strength to face his own fears and re-connect with the living.

The Awakening is not a typical zombie novel; it is, indeed, far more. It is a long, complex, multivalent, and ultimately powerful tale of awareness and acceptance. It is a coming-of-age novel, on the level of Robert R. McCammon’s Boy’s Life or Stinger, Dan Simmon’s Summer of Night, and Stephen King’s IT.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017