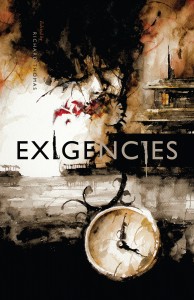

Edited by Richard Thomas

Darkhouse Press

June 9, 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Horror can serve a number of contradictory functions. It can destroy, and it can build. It can condemn, and it can commend. It can terrify, and it can heal.

For me as reader, some of the most effective horror narratives are ultimately redemptive. They show characters being torn down to their basics—their core beliefs, their understanding of themselves and of humanity—and by that process passing through evil at least relatively unscathed and moving into an increase of awareness. I can still remember the moment when I discovered how my first horror novel, The House Beyond the Hill, would have to end…with a moment of reconciliation and joy. Otherwise, everything the characters, living and dead, had suffered would have been useless.

At the same time, however, I can appreciate horror that opens vistas of darkness, because that, too, is part of being human. Fictionally, at least, some knowledge is too terrible, costs the questioners too much, and ultimately annihilates too much of their humanity; and their tales can only end in pessimism. Pet Sematary, with its horrific one-word conclusion, is one such.

The twenty-two stories Richard Thomas has included in Exigencies definitely fit into the latter group. They fully embrace the idea of neo-noir, in all of its connotations. As Chuck Wendig comments in his foreword:

We write the darkness onto the page because it’s clarifying. Detoxifying. The bleak, black stories we write—like the stories found in the pages ahead—are an act of us writer-types sucking out the snake poison and spitting it onto a window for the world to see.

The bleakness begins immediately, with Letitia Trent’s perfectly named “Wilderness”—which takes place in a modern airport and records its transformation into a moral wasteland, where innocent acts take on ominous meanings, where insecurity becomes terror, and where one woman’s inability to talk about her “monthly friend” leads to the unspeakable.

Joshua Blair’s “Monster Season” begins innocently enough, or so it seems, with an older brother tattooing a Superman “S” on his younger brother’s arm. That simple act, however, resonates darkly throughout the story of a town in the grip of Monster Season, and the nihilism required to rid society of its human monsters.

In Jason Metz’s “Single Lens Reflection,” a killer-by-assignment experiences what it is like being on both sides of a camera lens. In Nathan M. Beauchamp’s “The Mother,” an unnamed, nearly inarticulate creature confronts the loss of everything that makes sense in the world around it.

And on it goes, with stories by Heather Foster, Usman T. Malik, Barbara Duffy, Marytza K. Rubio, and others leading farther and farther in to darkness, death, and ultimate nothingness.

Individually, the entries fascinate and engage, at the same time purposely repelling with their starkness and bluntness. But that, in the end, is as it should be. These stories remind us of what extremes horror can explore, and that ultimately the exploration may be sufficient warrant in itself.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017