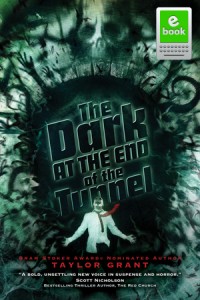

Taylor Grant

Cemetery Dance Publications

November 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

In “Gods and Devils,” the fourth of ten stories in Taylor Grant’s exceptional collection of short fiction, The Dark at the End of the Tunnel, Captain Vega considers his susceptibility to “Solipsism Syndrome” following months as the only fully conscious human onboard his space ship. The condition, the narrator notes,

…was a serious risk for anyone who spent long periods alone in space. It created the overwhelming feeling that nothing was real—or simply a dream. Sufferers had been known to feel so lonely and detached from the world they became utterly, and terribly indifferent.

As I read that paragraph on my Kindle, I highlighted the words; I was only about one-third of the way through the volume, yet already I recognized a key thematic element that, as strongly stated as it was, might ultimately connect all of the stories. Reading the final words of the capstone piece, “The Dark at the End of the Tunnel,” confirmed that sense.

Regardless of the convolutions and reversals each might take, every story dealt on some level with an “overwhelming feeling that nothing was real—or simply a dream.” For every character, that feeling leads to horror, death, and beyond. And in these stories “beyond” might entail gruesome and appalling visions of the transitory nature of life and the terrors of dark eternities.

“Masks” opens the book with a powerful portrayal of a man whose inner and outer lives begin to open on unwanted, almost indescribable vistas of pain and torture. As those images increasingly intrude into his relationships with others, he changes, at first subtly, then so radically that he no longer recognizes his own self and begins to understand that within — beneath the mask of humanity — lies horror.

“The Silent Ones” is among the most effective of the stories (although saying that suggests that some are ineffective — definitely not the case here). The narrator suspects that something is wrong when people seem to cease to notice him, and people he knows well forget him. Step by step — quite literally through much of the story as he wanders streets looking for something “real” — he is removed further and further from touch with humanity. For me, one of the most telling scenes occurred when he enters a late-night bar and realizes that the people there actually see him because they have already become as invisible as he. Some years ago, I spent a number of evenings at a fast-food restaurant nearby, writing. Only gradually did I see that the same people were always there, often just sitting, rarely eating. And I had become one of them! Coming across an analogous scene in a horror story was startling — but that was not the end of the surprises.

“The Vood” carries the image of isolation and self-abandonment to a hideous extreme. Grady lives — if it can be called living — in mortal terror of the Vood. The only protection he knows is light: if he is surrounded by light, the Vood in the shadows cannot devour him as it had his mother years before. Grant carefully withholds information about who and what the Vood is, delivering it in packets that move the story inevitably forward to the moment of discovery, an uncovering in more senses than one.

In “Gods and Devils,” an alien parasite has transformed almost all of humanity into Homo Hirudinea, human hosts who either carry and spread the parasite or feed it. Captain Vega is brought out of sleep stasis to face a crisis: one of the several hundred passengers aboard, who constitute the remnants of the human race, has awakened and, infected and hungry, threatens the lives of all aboard.

“Dead Pull” focuses on Brennan, a pet-store employee, a sadist, and — we discover almost accidentally — a murderer. By brutally wielding his presence and his life-or-death power, he has terrorized every animal in the shop into submissive obedience. But when he uses his authority to maltreat a young intern … well, things don’t go quite as Brennan anticipates.

In “Show and Tell,” young Jacob Campbell decides to explain to Mr. McDaniels why he had drawn the highly realistic — and horrifically detailed — pictures his teacher had confiscated. When he begins to open up about himself, his family, and his past, the counselor is at first mildly interested, though disgusted; as the story proceeds, Jacob pulls him into a story that ceases to be a story and leads — no surprise — to revelation, destruction, and death.

“The Infected” is the almost obligatory story of a writer whose story comes to mean more than he anticipates. In some ways it parallels and completes the depiction of isolation in “The Silent Ones,” only here the progression is slower, more cautious, and more devastating. Opening a Vietnam-era footlocker of his fathers, the character discovers an unfinished novel — unfinished by his grandfather, resumed and left unfinished by his father. If he can finish the novel, it will be the answer to financial and family troubles, if only the couple can survive the next little while. An opportunity for temp work arises — through the Tempting Agency — and life begins its inexorable assault on dreams.

“Whispers in the Trees, Screams in the Dark” is a neat modern recreation of a familiar folk-tale. Grant studs the backstory with clues, so it comes as no surprise that Blake must confront the ultimate wicked stepmother, in fiction and in life. It is a dark, finely honed story of a loner so desperate to be part of something — anything — that he is willing to bet the one thing most precious to him. He just doesn’t know that his life is also on the line.

“Intruders” focuses on Mason, another character convinced that life does not reveal all of its horror easily. He has become convinced that the “crazies” on city streets — the ones talking to themselves, arguing with themselves, gesturing to nothing at all — truly hear voices, not because they are schizophrenic but because there are creatures out there, out of dimensional sync with most human vision and hearing. In desperation, he seeks out an old lover and pleads for her help. She gives it. Sort of.

And finally, “The Dark at the End of the Tunnel.” Matt Jackson awakens from a decade of brain death to find himself ultra-rich, with a magnificent home in Malibu, a dream car in the garage, and the wealth to go anywhere and do anything he wants. But what he wants is to discover who he was before … before whatever made him go into cryogenic sleep. His physician assures him that full memory will resurface in a month or so, but Matt can’t wait. And in this case, he should have.

I’ve no doubt done the stories a disservice by compacting them to near bumper-sticker length. They are beautifully constructed and in the largest part well written (my only quibble with the collection is an occasional word choice or phrase — occupational hazard with being a retired English professor and an active editor). The stories read smoothly, as they should, since they deal mostly with twists on and distortions of reality, objectivity, perception, and individuality. There are, of course, scenes of gore and blood-letting and monstrous transformations and some that are not monstrous but manage to seem even worse; yet there is also humanity, even it if is only described by its increasing absence. Much is at risk in each story — not only a characters’ physical beings, but their hearts and souls as well … with emphasis on soul.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017