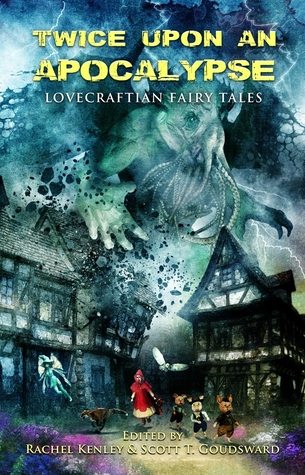

Twice Upon an Apocalypse: Lovecraftian Fairy Tales

Rachel Kenley and Scott T. Goudsward, Eds.

Crystal Lake Publishing

2017

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

What searchers after horror, what devotees of darkness could resist the temptation of a second volume containing such auspiciously titled tales as “The Pied Piper of Providence,” by William Meikle; “The Three Billy Goats Sothoth,” by Peter Dudar; “The Great Old One and the Beanstalk,” by Armand Rosamilia; “Let Me Come In!” by Simon Yee; “The Fishman and His Wife,” by Inanna Arthen; “The Little Match Mi-Go,” by Michael Kamp; “Follow the Yellow Glyph Road,” by Scott T. Goudsward; “Cinderella and Her Outer Godfather,” by C.T. Phipps; “Fee Fi Old One,” by Thom Brannan; or “The Legend of Creepy Hollow,” by Don D’Ammassa?

Or similarly titled tales based on classic stories by Hans Christian Anderson, Philipp Otto Runge, the Brothers Grimm, James Halliwell-Phillipps, and Charles Perrault…as viewed through the distinctly eldritch lens of the Lovecraftian cosmos?

Twice Upon an Apocalypse is, simply put, delightful—if tales of apocalyptic horror, cosmic devastation, and tentacular terrors can legitimately be so described. Each of the twenty-one stories builds upon fundamental fairy-tale motifs, up to and including the mandatory “and they lived happily ever after” (well, some of the characters do, at least; others stare into the face of utter and Outer darkness and are lost forever). At the same time, they incorporate the equally mandatory elements of the Lovecraftian world-view, with the return of the Great Old Ones, the rising of R’lyeh, and the consequent destruction—and/or consumption—of humankind.

And therein lies the fascinating charm of these stories. Fairy tales, as Gary A. Braunbeck reminds us in his brilliant introduction, represent absolute morality. There is an action and an almost instantaneous reaction. Many were originally monitory: don’t stray off the path or the wolves will get you (stemming from the times when wolves in fact roamed European forests); curiosity can kill; virtue in any of its forms is always appropriately rewarded. Many were also originally horrifying, as a glimpse into an unexpurgated translation of the Brothers Grimm will immediately attest, but only to make more distinct the moral implicit warnings.

The world of Lovecraft’s fictions is the polar opposite. In them, the universe does not reward virtue. It does not even notice virtue. It is implacably amoral. It not only does not care whether a character represents good or evil (which in themselves do not exist), it does not even know that it does not care. And if it knew, it still would not care.

Juxtaposing these contraries creates an intriguing texture. The old are made new; the old wooden bridge of “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” is replaced by a steel structure, guarded by the last remaining troll. Bluebeard’s castle is updated to a woodland cabin—in reality a “monstrous Victorian home” reminiscent of the mansions of the nouveau riche in Newport, Rhode Island—in Winifred Burniston’s excellent “Curiosity.” The opening words might place readers within a familiar fairy-tale world, but the following sentences immediately shift to the weird and the strange.

The technique perhaps shouldn’t work…but it does. The stories succeed as stand-alone tales; the anthology succeeds as an intriguing experiment in maintaining the fundamental—and contrary—values of both forms. Recommended.

- ‘eyes I dare not meet in dreams’ by Sunny Moraine - October 7, 2019

- Bill Hodges Returns in the Trailer for MR. MERCEDES Season 3 - August 21, 2019

- Release Details and Cover Art for Tom Savini’s Official Biography SAVINI - August 7, 2019

- IDW Publishing Announces Comic Book Series Based on Stephen King and Owen King’s SLEEPING BEAUTIES - July 29, 2019

- From Raw Dog Screaming Press: Preorder STEEL SHADOWS by J.L. Gribble - July 26, 2019

- Available Now from Crystal Lake Publishing: A new Poetry Collection by Stoker Award-Winners Linda D. Addison and Alessandro Manzetti - July 24, 2019

- From Raw Dog Screaming Press: Preorder On the Night Border by James Chambers - July 22, 2019

- From SDCC 2019: Watch the Trailer for New CREEPSHOW Series - July 19, 2019

- Evil Moves in Next Door in the Teaser Trailer & Poster for THE WRETCHED - July 18, 2019

- Hex Studios Unleashes A Legion of Demons In ‘For We Are Many’ - July 18, 2019